December 15, 2016

Human Rights Watch

(Istanbul) – Turkey’s government has all but silenced independent media in an effort to prevent scrutiny or criticism of its ruthless crackdown on perceived enemies, Human Rights Watch said today. The assault on critical journalism sharpened in 2014 but accelerated after the failed coup attempt in July 2016, denying Turkey’s population access to a regular flow of independent information from domestic newspapers, radio, and television stations about developments in the country.

The 69-page report, “Silencing Turkey’s Media: The Government’s Deepening Assault on Critical Media,” documents five important components of the crackdown on independent domestic media in Turkey, including the use of the criminal justice system to prosecute and jail journalists on bogus charges of terrorism, insulting public officials, or crimes against the state. Human Rights Watch also documented threats and physical attacks on journalists and media organizations; government interference with editorial independence and pressure on media organizations to fire critical journalists; the government’s takeover or closure of private media companies; and restrictions on access to the airwaves, fines, and closure of critical television stations.

“The Turkish government and president’s systematic effort to silence media in the country is all about preventing public scrutiny,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Keeping 148 journalists and media workers in jail and closing down 169 media and publishing outlets under the state of emergency shows how Turkey is deliberately flouting basic principles of human rights and rule of law central to democracy.”

Human Rights Watch found that the crackdown has not only targeted media and journalists associated with the Gülen movement, which the government alleges is a terrorist organization responsible for the July coup attempt, but also pro-Kurdish media and independent voices critical of the government such as the newspaper Cumhuriyet and its journalists. Human Rights Watch looked at the use of emergency powers, and at Turkey’s overbroad terrorism laws and pliant justice system as means of repression.

The report is based on 61 in-depth interviews with journalists, editors, lawyers, and press freedom activists, and a review of court documents relating to the prosecution and jailing of journalists and media workers.

Those interviewed described a stifling atmosphere for their work and rapidly shrinking space for reporting on issues the government does not want covered. Several of those interviewed were later arrested and are in prison pending trial or had to flee Turkey to avoid being detained.

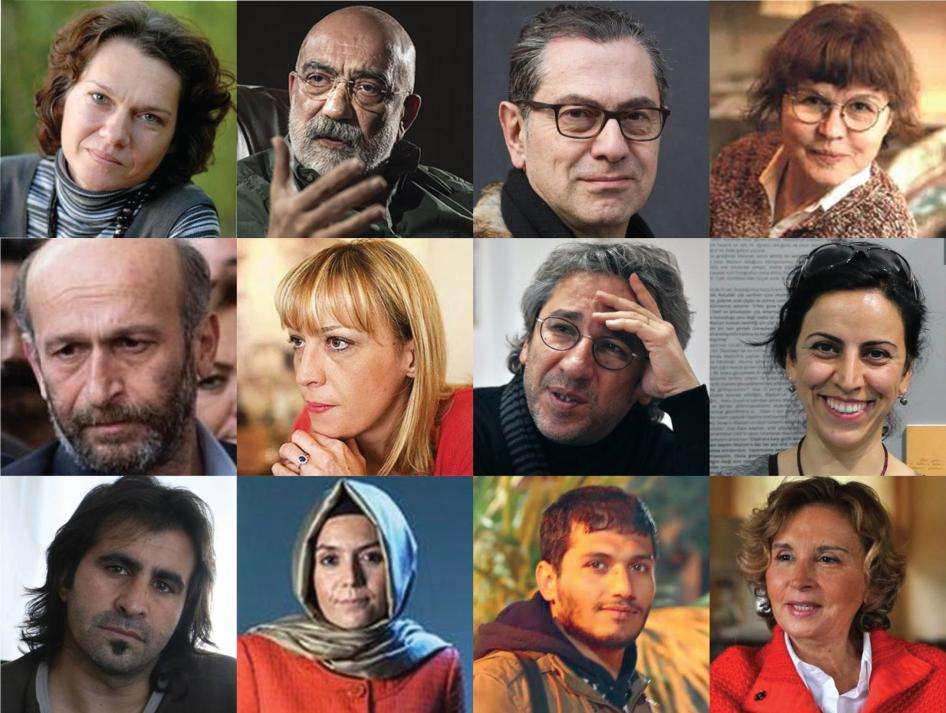

They include the Cumhuriyet newspaper columnist Kadri Gürsel and a former reporter for Zaman newspaper, Hanım Büşra Erdal, who are in prison, and a former reporter for Radikal newspaper, Fatih Yağmur, who left Turkey. Others whose cases are discussed in the report – like Aslı Erdoğan, Necmiye Alpay, and Ahmet Altan – were jailed during its preparation, Erdoğan and Alpay were indicted for terrorism crimes and will stand trial in Istanbul this month.

“In the past journalists were killed in Turkey,” one journalist told Human Rights Watch. “This government is killing journalism in its entirety.”

Journalists described limited access to the predominantly Kurdish southeast, where conflict has escalated since a ceasefire between the government in Ankara and the armed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) broke down in July 2015, leaving a tentative two-and-a-half-year peace process in tatters. Journalists working in the southeast face serious risks and have been threatened, arrested, and ill-treated by members of the security forces and police, and even the public, in the course of reporting.

However, over the past year physical attacks on journalists have not been confined to the southeast, as demonstrated by the shooting of the former Cumhuriyet editor Can Dündar, the assault on the CNNTürk journalist Ahmet Hakan outside his home, and the attacks on the Hürriyet newspaper. Journalists interviewed were sceptical of whether the authorities were willing to investigate threats and physical attacks thoroughly, or of whether trials against suspects would deliver justice.

Over the past year, the government has engineered the takeover of privately-owned media and other organizations by appointing government-approved trustees to run them. This is a serious misuse of the law on trusteeship, a violation of the right to private property, and, in the case of the media, a policy of deliberate censorship aimed at suppressing critical and dissenting voices, Human Rights Watch said. In the period following the failed military coup, the government opted for full closure of newspapers, news agencies, radio, and television stations using state of emergency powers.

In light of the findings, the Turkish government should end detention and prosecution of journalists based on their journalism or alleged affiliations; ensure that any closures of media during the state of emergency are only as a last resort following due process; condemn and ensure prompt and effective investigations of attacks on journalists; stop misusing the Penal Code to put media under trusteeship; and bring the Penal Code and Anti-Terror Law into compliance with Turkey’s international human rights obligations.

The US and European Union member state governments, the Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and United Nations Human Rights Council should use their leverage to press the Turkish government to respect media freedom, Human Rights Watch said.

“Free and independent media help promote the free flow of ideas, opinions, and information necessary for political processes to function, and serve as a critical check on executive authorities and powerful actors linked to them,” Williamson said. “The Turkish government’s erosion of media freedom harms Turkey and its democracy as well its international reputation.”